After their large-scale introduction to the battlefield in the 1950s and 1960s, helicopters greatly impacted how wars were fought. At the same time, it was clear that they were inherently vulnerable, and means were developed to make them more survivable. Since then, new tactics, high speed, a wide variety of countermeasures, and even stealth technology, have been adopted in different applications and to varying degrees. However, a U.S. effort to create a protected helicopter that was essentially a flying armored fighting vehicle was less successful. This is its story.

In 1967, the U.S. military was mired in the Vietnam War, and helicopters were playing a hugely important role. Of the around 12,000 helicopters used by the U.S. armed forces in Vietnam, more than 5,600 were lost, according to figures from the Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association. Meanwhile, manufacturers in the United States were looking for ways to create helicopters that would have a better chance of surviving both in Southeast Asia and on even more highly contested battlefields.

In the same year, Sikorsky was developing a new type of aircraft armor that would provide protection to helicopters against ballistic threats. In Vietnam, helicopters were repeatedly subjected to gunfire when they were operating in and out of ‘hot’ landing zones. On the ground, they were the targets of mortar or rocket attacks.

Sikorsky’s new dual-hardness steel armor was both robust and light enough that it could be used as the basis for building the helicopter’s primary structure, rather than adding it on later.

At the same time that it was working on this innovative armor, Sikorsky was developing its Advancing Blade Concept (ABC), which promised helicopters that would be much faster than using traditional rotors.

ABC was just one of many efforts at this time to dramatically enhance the performance of rotorcraft, with others notably including compound helicopters, which combined the familiar rotors with a wing and some kind of auxiliary propulsion to generate higher speeds.

Sikorsky’s ABC was an alternative to the compound helicopter and involved a contra-rotating main rotor allied with auxiliary propulsion to propel the aircraft in forward flight. Using this rotor arrangement removed the problem of blade stall, which otherwise limits the speed of conventional helicopters, and obviated the need for a tail rotor.

For a heavily armored helicopter, ABC promised several advantages. It was more robust and simpler than a conventional helicopter configuration, making it better able to withstand damage, especially since the very vulnerable tail rotor and its transmission were omitted. High speed was less of an issue, since the armored helicopter was intended to survive ballistic attacks, at least to a certain level, rather than evade them. But the ABC arrangement was also notably agile, which would be useful for maneuvering in combat.

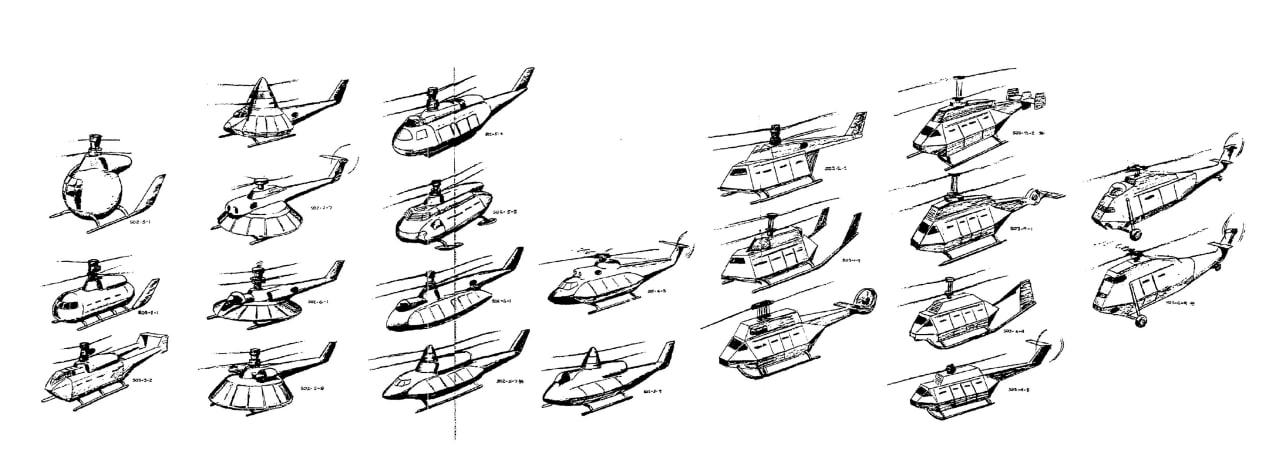

Sikorsky began to look at two armored helicopter options.

The first of these was the Aerial Armored Reconnaissance Vehicle (AARV), which was a two-seat scout. It was envisaged as a successor to the U.S. Army’s Hughes OH-6 Cayuse and Bell OH-58 Kiowa. These had been procured under the Light Observation Helicopter (LOH) program and saw extensive use in Vietnam.

The AARV program was funded by Sikorsky and the Army over a period of two and a half years. Playing a significant role was the Army Materials & Mechanics Research Center, which helped develop the half-inch-thick dual-hardness armor needed for the helicopter’s airframe.

From its total weight of 6,800 pounds, the dual-hardness armor accounted for around 1,800 pounds.

Since this was very much breaking new technological ground, much effort was put into working out how best to cut, join, form, and finish the helicopter using this material. After this evaluation, a fuselage mock-up was constructed and then subjected to ballistics testing.

In overall configuration, and apart from its ABC rotor arrangement, the AARV was fairly conventional and simple. The fuselage was notably angular, with a prominent chine line and a faceted appearance. While this kind of design would reappear on stealthy helicopter concepts, here it was utilized for better protection against ballistic fire.

While the main fuselage was built from dual-hardness armor, the empennage was made from aluminum. The tail featured an inverted-V configuration.

With a length of 25.4 feet and a fuselage height of 4.5 feet, the AARV was even more compact than the diminutive OH-6, which was 30.3 feet long and 8.1 feet high to the top of the rotor mast.

Unlike in the other ABC proposals of the company, the AARV didn’t have auxiliary propulsion, being powered by a single Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6 turboshaft. Rated at 1,175 horsepower, this would have given the helicopter a top speed of 150 knots.

In trials, the helicopter’s airframe was able to withstand 7.62mm caliber gunfire at point-blank range; at longer ranges, 50-caliber projectiles also failed to penetrate it. As well as the airframe armor, advanced ballistic glass ‘transparent armor’ was used for the cockpit transparencies.

The AARV would also have had provision for its own weapons, with options to install a 7.62mm Minigun on a telescopic mounting below the fuselage, while pods of unguided rockets could be pylon-mounted on the side of the fuselage.

Although a full-scale ABC rotor system was successfully tested in the NASA Ames wind tunnel in 1970, the AARV project didn’t progress any further, with the Army instead concluding that this technology would be better used in a high-speed platform.

Sikorsky completed a high-speed ABC demonstrator, the S-69, but this also failed to lead to any production aircraft.

In the meantime, the same ‘armored helicopter’ thinking that led to the AARV was also used as the basis for another Sikorsky project, the Aerial Armored Personnel Carrier (AAPC).

Essentially a scaled-up version of the AARV, the AAPC was built around a box-like armored cabin with accommodation for 12 soldiers. The rotor diameter was increased to 40 feet, compared to 35.4 feet for the AARV. At least two different empennage arrangements were studied, one being an inverted-V in which the tails were attached to the rear of the landing skids, and the other being a more conventional horizontal tailplane with vertical endplates.

The AAPC progressed as far as a full-scale mockup, but the Army wasn’t interested in pursuing it further. As it is, the AAPC makes a very interesting comparison with the Mi-24 Hind, which was the Soviet response to the similar kind of requirement, although it stressed speed and firepower over protection.

The AARV and AAPC might have faded into obscurity, but the Advancing Blade Concept made a powerful comeback, many years later.

Sikorsky returned to the concept with its X2 demonstrator, first flown in 2008, and intended to prove the technology, again. Once more, ABC was seen as a way of unlocking speed and maneuverability, and increasing helicopter survivability under battle conditions.

The X2 led to the S-97 Raider, which was a more production-representative aircraft, which took to the air in 2015.

The S-97, in turn, paved the way for the promising RaiderX, which was widely seen as being a potential frontrunner for the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft (FARA) program, that aimed to supply the Army with a high-speed new-generation scout and attack helicopter. FARA was cancelled early last year.

Meanwhile, the RaiderX fed into the enlarged SB>1 Defiant, which lost the Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft (FLRAA) tender to a design based on Bell’s V-280 Valor next-generation tiltrotor. It was a very high-stakes competition, our analysis of the results of which you can read here.

While APC technology might have to wait a while longer to find its way into a production helicopter for the Army, there is little doubt about its potential. Years of testing have demonstrated impressive speed, agility, and hot and high performance, with the ability to pack this all into a relatively small footprint.

Ultimately, the AARV and its troop-carrying counterpart were destined to be footnotes in the colorful history of Cold War U.S. helicopter designs. However, they played a highly instructional role during a time of rapid development in rotorcraft technology, and one that points to continued concerns about how best to ensure survivability once thrown into battle.

Contact the author: [email protected]